A rare gem. Review of The Great Zimbabwe

Related Products

There are games and there are games. Some games can be seen everywhere and are played by everyone, while others are shrouded in mystery and ritual. It's like comparing a mass-market soft drink to a vintage wine—some are readily available and give instant but quickly forgotten pleasure, while others are rare and unique experiences. Splotter Spellen games belong to the last category.

I was first introduced to Splotter Spellen when a collector unceremoniously presented a copy of Roads & Boats and carefully peeled off its protective film to reveal what at first glance looked like a collection of uninspiring components. With the playing time and price triple what I was used to, I remained lukewarm to his enthusiasm. The lack of Splotter Spellen games at all my gaming gatherings further confirmed my skepticism.

But the more I learned about games, the more Splotter Spellen's games stood out in discussions of great games. Could a game like this fill a gap in my already limited collection? Maybe there was one game that was highly rated by a few influential geek friends with a reasonable play time (90-150 min) and weight (3.7). When I was offered to buy a used copy from the aforementioned collector, it was time to discover the world of Splotter Spellen!

ECONOMY OF THE GREAT ZIMBABWE

The Great Zimbabwe is a good representation of the type of mechanics that I've come to find characterize many of Splotter Spellen's games: build a shared infrastructure and use it to make more money than your competition. In The Great Zimbabwe, the shared infrastructure consists of artisans who transform resources into goods, which are then used to build monuments. The higher the monument, the higher your score. Let's take a closer look at the different links in this economy.

Assets

Resources are provided during training (clay, wood, ivory and diamonds). The playing field consists of several 6x6 squares, some of which contain resources.

Artisans (potters, wood carvers, ivory carvers, and diamond cutters) are placed by the players themselves. They must be placed within reach of resources (no more than 3 squares).

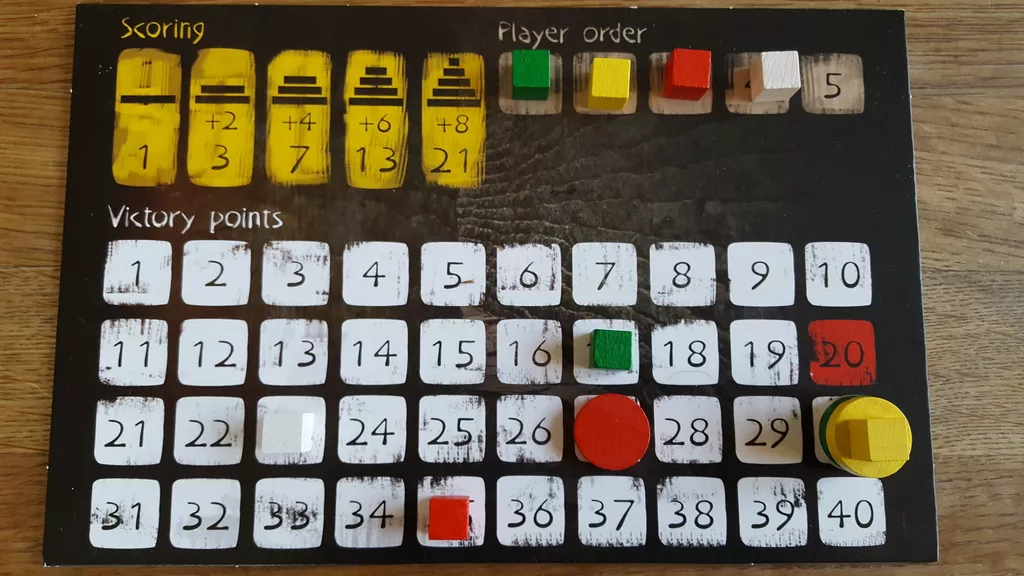

Monuments are also set by players themselves, and must be placed within reach of masters (to enable additional levels). Each additional level requires 1 unique item, but increases your score exponentially (1 for level 1, 3 for level 2, 7 for level 3, etc.). The higher you want your monument to be, the more craftsmen you need near it.

The reach of the crafter (but not the resource) can be extended by using the monument as a hub, thus allowing for longer routes to obtain these precious goods. The connected sea squares work as one big "hub", which makes the adjacent land squares especially interesting for placing artisans and monuments.

Limitation

Of course, this economy does not have unlimited assets, so let's continue by looking at spending and other limits of the Zimbabwean economy. Thematically, all prices are paid in cattle heads.

- Artisans cost livestock, but earn victory points when placed. The game has a limited number of masters.

- Artisans cost livestock to use (paid to the player who placed the craftsman). Resources used by wizards are free but limited throughout the round, meaning once used they cannot be used again until the next round.

- Monuments cost 1 cattle to use as centers (paid before supply).

MAIN CHALLENGES

This simple economy sets the stage for interesting interactions between players. You need to make sure you have access to both livestock and crafters to expand your monuments. Maybe you want to bring in a craftsman that only you can reach to secure the item? Maybe you want to place a crafter within range of other players to provide livestock? Or maybe you will focus only on the masters or only on the monuments? The designer could have stopped there and had a simple, almost solvable puzzle. But no, he decided to throw in just the right amount of wrenches to make the game more difficult.

ADDITIONAL CHALLENGES

Increased requirements for victory

The winning requirements are not fixed, but can change throughout the game and be different for different players. One example (and more will follow) is the acquisition of technology, which is a prerequisite for the placement of certain masters. The technology is free, but it increases the number of victory points needed to win. This adds some interesting challenges.

First, you can choose between a "cheap" strategy (ignore the "engine" and keep the win requirement low) or an "expensive" strategy (build the "engine" and accept that the win requirement will be harder to achieve). Remember that the bulk of your victory points will come from monuments, and while higher monuments increase your score exponentially, their cost will also increase as they require more unique resources.

Second, it is more difficult to determine who is leading. Is it a player who scores a few points per turn and is close to a low win requirement, or is it a player who scores a lot of points per turn but is far from a high win requirement? Or, in gamer parlance, who can you afford to help and who should you screw over?

PRICES

The prices for crafters' goods are not fixed, but are set by the players between 1 and 3. This is pure supply and demand. Which will make you the most: low price and high volume or high price and low volume? At what price will your profit from livestock be greater than your opponents' profit from goods? And what happens if the opponent puts a competing master? To make your decision even more painful, once the price is set you can only increase it, not decrease it.

SECONDARY ARTISANS

Do you think games like Power Grid and Santiago where you can strip your opponents of resources are evil? Then you haven't met the secondary artisans of The Great Zimbabwe. A secondary craftsman will use a resource AND a good from another ("primary") craftsman. To make a more valuable product? No, make the products of the primary craftsman unsuitable for monuments! A well-positioned second crafter can make goods more expensive and/or rarer and completely destroy the other player's economy. So much for product development!

AUCTION

Given that resources are limited in each round, turn order is important, so naturally there is a game around that as well. However, The Great Zimbabwe bet is not only about rewarding the highest bidder, but also about distributing the cattle among the players. He accomplishes this by placing bets on certain fields (1st cattle on 1st field, etc.) and then returning the cattle to players (1st field to highest bidder, etc.). Do you really want to make a high bet knowing that other players will eventually win most of your bet? Did I mention The Great Zimbabwe is a very evil game?

SPECIALISTS AND GODS

I'm not a fan of cards in games. They often dictate your strategy randomly and lead to gameplay where players are looking more at the card tables than the field. But The Great Zimbabwe is not like that.

- First, the cards are limited - the game uses only 5 specialists and 8 of the 12 gods, which are known in advance to all players. As such, their potential impact on the game is transparent and predictable.

- Secondly, the cards are not random, but are chosen by the players themselves (at the cost of increased requirements to win). This way you can adapt your strategy to your choice of specialist and/or god and vice versa.

- Third, given the interconnected economy, other players' choices will have a profound effect on gameplay and what you should consider in your own strategy.

Let's look at some examples:

- Elegua and Engai: The player receives cattle from the stock. This can be expected to increase the total number of livestock in the game.

- Eshu, Kamata: Players get increased range/payout when hubs are used. This can be expected to increase distances in the game.

- Gu: The player gets cheaper innovations. This can be expected to increase the number of masters in the council.

The result is that the presence or absence of a specialist or god can dramatically change the game from game to game. New players are saved from the surprise of a god unknown to them, while experienced players are rewarded by knowing how a god known to all players can affect the game. In my book, this is an example of cards made right in the game.

SO WHAT'S ON THE PLAYER'S HEAD

There is a lot to think about in The Great Zimbabwe .

- First, we have a tender. If I bid high, will I have enough cattle left to do what I want to do in the field? If I bid low, will I have enough left to work the field after the other players have taken turns?

- Second, we have a choice of god and/or specialist. What abilities are good in this particular game and are they worth the increased win requirement? Maybe I should wait another round before making a decision, but what have they been plucked by another player before then?

- Thirdly, we have a choice between masters or monuments. If I choose masters, should I help myself with livestock (from other players with my masters) or goods (with my master)? If I choose monuments, I increase my score in the short term, but do I have enough livestock to expand them in the long term?

- Fourth, if I choose a master, who should I choose and where should I place it? Is proximity to many resources or many craftsmen best? Is low price or high price best? What other masters and prices are there on the board?

- Fifth, if I choose monuments, should I focus on a few large monuments or many small ones? A few big monuments increase my score faster, but are there enough resources? Many small monuments are cheaper, but is there enough time?

- Sixth, there is the question of what wizards and resources I should use. If I bring in my own masters, I get my money back next round. But maybe it's more important to use wizards than other players to strip them of their goods?

- Seventh, there is another question about when is the right time and where is the right place for a secondary master. To give myself more livestock or goods that only I can get, or to block other players from using basic wizards? Or both?

- Eighth, if I'm behind, how can I best disrupt the economy so that everyone else can catch up? (This is one of the many things I'm still learning.)

So many things to think about, but so little time - the game usually only lasts 6-8 rounds!

COMPONENTS

Finally, a few words about design. I hinted earlier that Splotter Spellen was often criticized for its poor components. Although the components of Great Zimbabwe can be a bit contrived, they get the job done and the iconic icons and images based on authentic African art are simply beautiful. I definitely wouldn't trade components for plastic cattle.

CONCLUSIONS

Games are so often described as having interconnected mechanics and subtle interactions that the words begin to lose their meaning, but The Great Zimbabwe manages to bring them to life. This isn't a game about doing things that another player might have wanted to do. No, it's a game of perfect information, where everything that happens happens because of the actions of the players. You can't attack other players directly, but you can "stealthfully" destroy their base. However, all of these mechanisms are so well-tuned and balanced that the game itself resists any attempt to break it. As a designer, I can't help but wonder how many hours of testing went into The Great Zimbabwe to achieve this perfection. Jeroen Douman and Joris Wirsinga have created a masterpiece, and I humbly bow my head.