New technologies in the board game "Return to the Dark Tower"

Related Products

Growing up, I didn't have a lot of variety of board games. Those who were in our family were divided into three camps. We had classic games like Risk and Monopoly, also known as "boring games". A friend of mine played complex scrolling games that required a greater investment of time than my infrequent visits could provide. And there were paranormal games capable of ripping apart the fabric of reality like a popped pimple and letting diabolical hordes into our world. These included spirit boards and cards for divination.

But later, during a break between episodes of Duck Stories, I saw something new in a commercial. In bright colors and with a charming voice-over, the video boasted something more like a mountain of plastic than a game. But it was all moving. It made sounds. The gameplay was like a hurricane. I had to get it.

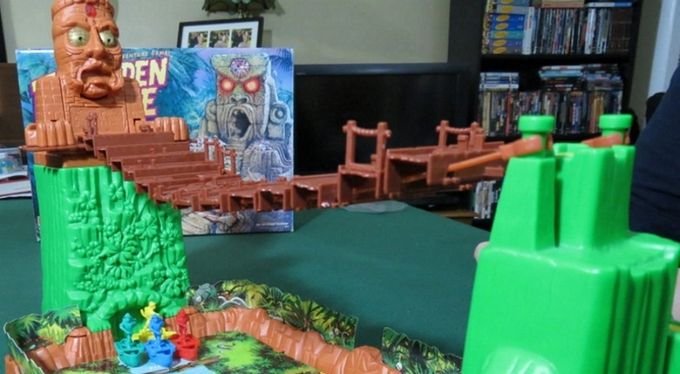

It was the game Forbidden Bridge. Her commercial stuck in my memory. And that Christmas was my first introduction to a mechanical device as part of the gameplay.

One of the main joys of board games is unboxing them. This is a childish hobby, reminiscent of unwrapping a gift. You carefully cut the tape that secures the edges, afraid to tear it off and leave a scar on the box. You remove the packing material, enjoying the smell of either ink or earth, which you will realize decades later is not much different from the smell of a long-buried clay shard. You untwist the metal wires that hold the parts in place as securely as the seals on a cursed sarcophagus. My grandfather gave me a swiss army knife at a very young age, and it came off one of these procrastinations and cut my thumb. With tears in my eyes, I barely convinced my father to just put a Band-Aid on the wound instead of stitching it up in his basement office. He agreed, but confiscated the knife until I was ten years old. Carefully taping the wound, I returned to the box. The sore thumb, the long assembly of those numbered plastic boards, the confiscation of my prize folding knife were all worth it. At that point, I was putting in too much effort. Finally the game was ready. The adventure began.

And then we played this thing.

Even as a kid, Forbidden Bridge disappointed me. Even then, the throw-and-move mechanics seemed shallow and unsatisfying to me, and that's pretty much all the game had to offer. You roll the die. You are moving. The game didn't even allow you to first leave the cube and then choose which figure to move. In addition to rolling a die for your explorer's movement -- by boat, on foot, and eventually jumping from plank to plank on a swinging bridge -- you roll a die to play out events. Stealing precious stones and pushing opponents are the most boring options. But even the most exciting event, where you click on the idol's head and watch the bridge sway back and forth, possibly dropping another hapless adventurer into the river below, somehow feels tasteless and primitive. The grinding of the gear mechanism was heard. This sound effect was harsh and unpleasant. The mechanism looked so flimsy that it seemed like it would take one push from its older cousin to break completely.

Soon the bridge was repurposed. It was not so much a game as a toy. Lego Samurai could fall off this bridge. Playmobil titans loomed in the waters below. Every few years we gave the game another chance. I've read this rulebook more than anyone else. But it never helped. The suspicion that all such games with mechanisms are simple trinkets stuck in my head for the rest of my life.

The original Dark Tower had ads too. But I never saw her as a child. I only had a vague idea of Fireball Island, another project that was also later revived by Restoration Games. But that time I had enough. A few other board games have been on my desk—sorry, my nursery floor—but never again have I ventured into games with a knee-high mountain of plastic. When Restoration Games announced the release of Return to the Dark Tower, I had the same ingrained suspicion. What rubbish, I thought. What a waste of space and money.

But I was wrong.

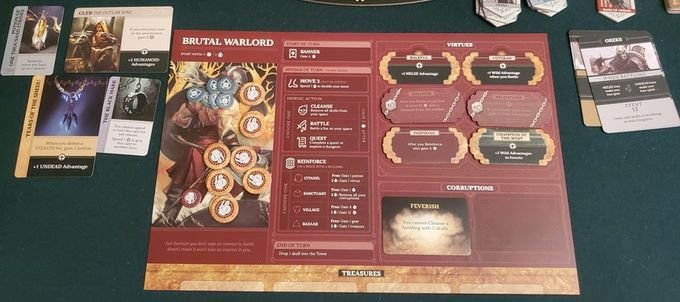

Right now, Return to the Dark Tower offers something similar to the original game. See, there's this dark tower, and you play as a group of heroes, yes, and your task is to defeat the evil within it, right? There's a lot of familiar flavor to the game's monsters and enemies, but it's not an attempt to reinvent the wheel [of time] that we've used so often before. From the point of view of experienced board players, the game may seem quite ordinary.

For now, we are not going to consider the plastic giant on the table. Like the bridge in Forbidden Bridge, the tower in Return to the Dark Tower is a fully mechanical device. This thing is huge. It obscures the view of the field like some kind of supernatural eclipse. Connected to your phone or tablet via Bluetooth, the tower screams and roars when enemies attack. Sometimes it buzzes and spins, scattering deadly skulls and spreading distortion across the four kingdoms. Sometimes it informs that it is necessary to remove the print. At such moments, the tower glows and pulsates, revealing a grim maw that spews out skulls or, worse, reveals a glyph that increases the cost of one of your heroes' actions. Sometimes this is accompanied by mechanical sounds, the motor gives itself away. But does it look cheap? Not a bit

The tower itself is only a small part of what sets the game apart from something like Forbidden Bridge. The more important factor is that it's a real game, and an awesome one at that. Forbidden Bridge offered only a mechanical trinket instead of a game. Return to the Dark Tower ditched that cheap approach. Here, the device and the game are inseparable. They complement each other. And asking which of these is more important is like asking which scissor blade cuts better.

Part of my misgivings about Return to the Dark Tower was that it wasn't limited to just one mechanical device. The original game used a computer built into the wall of the tower. These days, it's getting harder and harder to wow kids with computers, let alone displays built into everything you can find. Instead, Return to the Dark Tower works over a wireless network.

I'm agnostic when it comes to board games with digital components. I play board games in part to distract myself from screens, and like anyone else whose digital possessions have been lost at least once due to technical failure or licensing issues, I'm reluctant to give up too much of my board games to digital apps and other upgrades . I still have the Forbidden Bridge. If its original incarnation in 1992 had required an app, there's no telling if the thing would have supported the operating system I use today.

But I will say that this is the most enjoyable digital part of a board game I've ever played.

Automation is an important part of program integration. When your turn ends, you throw the skull into the tower. The program instantly understands that your turn is over and starts playing out the events. These events are far from how they are presented in most board games. This is not just a drawing of some card. Sometimes nothing happens at all. In other cases, monsters appear or attack, or do something strange and deadly. Sometimes the villain lurking inside the dark tower spawns threats or quests that you need to watch out for. After all, these threats can ripen and punish if you do not deal with them in time. In turn, you can hire companions. They provide benefits by themselves and also generate ongoing story in the game world. Such a sir drives the enemy to a more profitable territory; Lady Elven Face allows you to spend a resource to gain a skill. Before long, an event phase brings together three or four disparate branches, all acting in concert to create a world that breathes life into its farthest reaches. Perhaps a card system like the one in Robinson Crusoe could handle this, where threats return over time and any choice can have lingering consequences. But even in this case, such a decision would be cumbersome. You'd have to randomize the timing and appearance of the distortion, determine the enemies and their actions, slowly develop the villain's overarching plot, not to mention keep track of the status of your companions and any ongoing quests and dungeons. It's just too much. Since the game works with the app, you don't have to worry about that.

The same applies to other functions of the program. Combat, for example, has common roots with card games. To defeat an enemy, you move to their location and start a battle. The app will then provide you with a deck of cards. You pick a few, upgrade them with advantage points gained from your hero's skills, terrain, and more. If the battle was fought physically, it would require a lot of cards. A lot of cards. Decks for each monster and their variations are often with uncertain results. You see, the battle here is like a game of luck. Each enemy card has a value. To defeat a bandit, you may need to kill ten of your warriors, spend spirit tokens, or scrap a few potions. You can weaken an enemy card and the effect will change, but not always in the way you expect. Perhaps now the enemy will demand to sacrifice only five soldiers. Maybe another buff will drop that number to zero, or you'll get some warriors altogether because you'll kill this beast without taking any casualties. The bottom line is that with the help of the program, the game easily copes with these issues. Nothing will be lost sight of. You'll never go through five decks of nearly identical "Attack C" cards looking for the right knockback only to realize you've confused them with a deck of "Surge D". Instead, all your attention is focused on making the most of your strengths. Should you waste advantage on weakening a card you can implement but don't want to? Or should you wait and see if the next card hits you even harder? Sometimes a successful outcome results in you avoiding damage entirely. It's frustrating at times, especially when you've been saving your advantage for parrying a powerful blow that never lands. With the help of digital technology, the battles in the game have been brought to perfection. You think about how it "cuts" you, how to avoid more serious "cuts", not whether you can find the sword at all.

Moreover, the program improves the gameplay, not just replacing components with digital counterparts. Take, for example, dungeons. These are permanent locations where you'll have to explore room by room until you discover an objective or retreat prematurely. Backtracking means you can try the dungeon again later. All progress will be saved at this time. Empty rooms will remain empty. Enemies and artifacts will remain defeated and looted. As with combat, the focus here is on your character's current stamina and resources above all else. Return to the Dark Tower has quite a few items and little things to manage without having to lay out the cards every time you complete a quest. By handling all of these things in the background, the app increases the scope of what's going on without requiring any control at all. Even those parts that could be replaced with physical components are implemented more interestingly, because they are connected to this digital master.

As a result, I had a surprisingly enjoyable experience, unlike those adventure games that turn me away from the genre. While games like Descent can spend more time on component placement and other fiddling than playing the game itself, Quentin Smith mentioned in his review that Third Edition made him feel like a "level uploader" - "Back to Dark". "tower" takes a very important step — turns away from such a path.

Except for the Dark Tower, anyway, though that's rather to her advantage. Like a good antagonist, the Dark Tower is always in your head. Not only because it keeps throwing skulls all over the field, but because it's a huge piece of plastic that screams at you from time to time. She is big. It looks convincing. It blocks the light. When someone on the other side of the table asks if you can reach an enemy or a dungeon before it's too late, the tower prevents you from seeing the optimal route, forcing you to crane your neck or refine your path. It's annoying, but it's annoying in the sense that it emphasizes the tower's intervention in two worlds at once. One might assume that the game version of the tower is made to some extent for scale. Its size on the table represents a threat, inspires horror, it hangs over the head like an ax. Despite the whole menagerie of available enemies, each of which is dangerous in its own way, the real villain is always the tower itself.

I played this game like an obsessive. I bought a battery. I ordered the extras. I've never had to do either of these before for a game about adventurers and roaming monsters.

There is an irony in this. With the tower and its annex so grand and creepy, Return to the Dark Tower is a breeze to play. This is a case where a gimmicky in-game gadget can be more than just a marketing ploy. It is a labor of love and competence that elevates its creation to an object of wonder and awe. Surprise and awe from horror, but it is still surprise and awe. Developing in different directions, the game collected the best features of the genre and polished them to a shining shine. Roaming through fantasy lands, clearing cities, defeating monsters and acquiring all sorts of trinkets has never been so enjoyable.